Report: Major media outlets kept Maduro’s abduction program secret, but they withheld reporting.

The New York Times and The Washington Post reportedly sought to “avoid endangering US troops.”

The New York Times and The Washington Post reportedly sought to “avoid endangering US troops.”

The New York Times and The Washington Post reportedly sought to “avoid endangering US troops.”

The New York Times and The Washington Post reportedly sought to “avoid endangering US troops.”

The New York Times and The Washington Post reportedly sought to “avoid endangering US troops.”

The New York Times and The Washington Post reportedly sought to “avoid endangering US troops.”

The New York Times and The Washington Post reportedly sought to “avoid endangering US troops.”

Post de Facebook con multiples imagenes

💬 “Quiero un aumento.” 🤯 “¿O querés cobrar el doble pero pagar la mitad de todos los servicios e impuestos?” Cuando el sistema termina ganando más que los emprendedores o trabajadores, el problema ya no es entre jefe y empleado,…

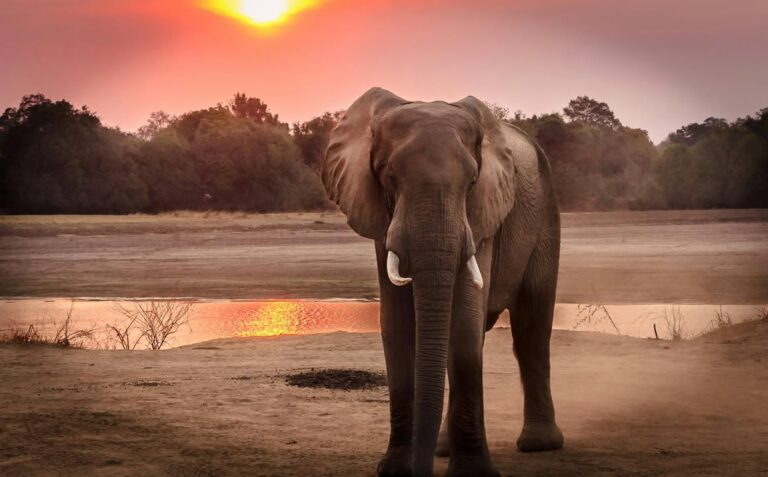

estadio deportivo

Post de Facebook con multiples imagenes